I have never had an easy relationship with my body.

I was virtually unaware of it when I was young. I was an active child, brought up in the age when TV was the only screen we had and we watched an hour after school and a movie on the weekends. The rest of my time was spent alternating between running around the backyard with my siblings and reading as many books as I could get my hands on. The combination of very little media influence and a generally healthy upbringing meant I rarely thought about my appearance, my body was just the thing that allowed me to do cartwheels, ride my bike and wear the Jurassic Park t-shirt I borrowed from my brother so many times that my parents had to buy me my own.

In my early teens my body started to change, as bodies do at that age. I gained a conscious awareness of it – how it looked, how it responded, how it always seemed uncomfortable to inhabit. I went through stages of extreme dieting where I honestly believe I could have disappeared entirely and still felt like I took up too much space. I’ve been afraid of the attention my body attracted, battled it when it broke down physically with chronic illness and lamented it for aging when society told me I should be young forever.

Eight (or so) years ago I started taking conceptual self-portraits. Initially it was simply a matter of convenience. I wanted a model in my images, but I was too scared to ask anyone to pose for me. I considered myself a character in the images, they we’re self-portraits in only the technical sense and so, when I edited my images, I adjusted my body whenever I didn’t like how it looked.

A few years in, my work became more personally driven. I was still aiming to express a concept but the ideas were specifically mine. My self-portrait practice became more immersive – what I experienced in front of the camera became just as integral to the process as what I did behind it. Despite this, I still struggled to accept my appearance in my photographs. I discarded many shoots and ideas entirely because I wasn’t happy with how my body looked in the pose or outfit I’d chosen. Other times I would choose a final image based on the shot where I thought I looked the best rather than the one that best portrayed the concept and wondered why my work felt shallow and lacklustre.

As I delved deeper into my craft and sought out ways to make work that was more than just a pretty picture, I came to a realisation.

Self-portraits are not actually about what you look like.

Self-portraits are an avenue for creative expression. They’re about feeling and perceiving, about exploring who you are and how you fit into the world, what you believe, what you value, what you stand for and what you struggle with. Self-portraits are about finding your voice and speaking it, by yourself, for yourself.

I’m not interested in shooting images where I do nothing but fit into the acceptable definition of attractiveness and rely on that alone to make beautiful art. In fact, I don’t even want my art to always be beautiful, at least not in the traditional sense.

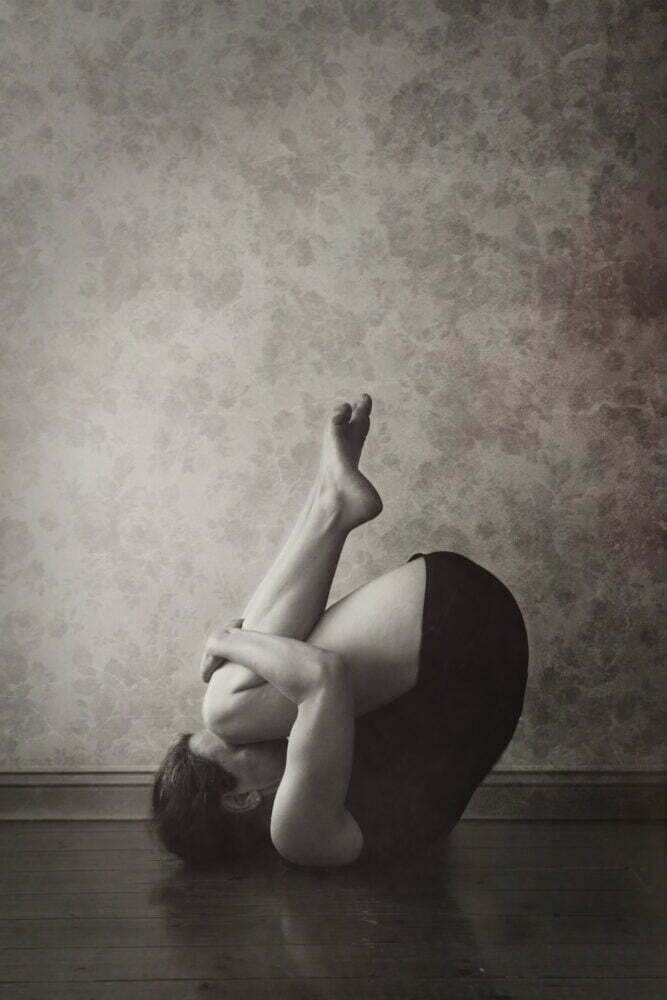

I want to make art that is evocative, expressive and emotional. I want honesty, curiosity and exploration. I want tension and tenderness and defeat and growth. I want all the messy parts of being a human, interpreted through my lens.

It has also only been very recently that I’ve realised that, perhaps, self-portraiture could become a way of starting to heal my relationship with my body, a place where I recognise what my body can do, over what it looks like, and what it can allow me to achieve. Finding some level of self-acceptance opens doors to a greater creative practice, allowing me to use my body as a visual tool in my images to tell the stories I want to tell.

Through this new way of thinking, I’ve discovered other self-portrait photographers using their art as a form of therapy. Their images are beautiful, because they are honest, stripped back and raw. They openly admit that it’s a practice, a work in progress, that they struggle, that they doubt their work, but still they persist. I find comfort that the process is worth pursuing even when it becomes difficult, that they have achieved some peace with their bodies compared to the point they started at.

Self-portraiture has been a journey for me, of self-exploration, discovery, acceptance and evolution over time. It’s a practice, with no finish point, something where I’ll keep creating, keep evolving and keep learning.

I don’t pretend to have it all figured out, in fact, I’m certain I don’t and that’s kind of exciting because it means there’s more to be gained. And somehow, I hope by exploring and starting to make some peace with my body, I can give others permission to do the same.